Tuesday, February 28, 2006

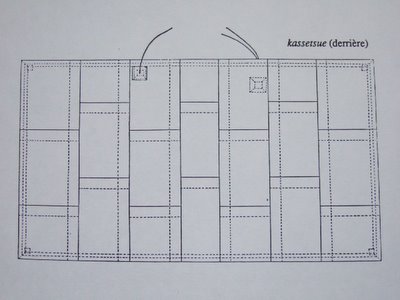

“The larger is three cubits long by five cubits wide (…) it has only seven stripes , each with two long segments and one short segment”

Kesa-Kudoku, Dogen.

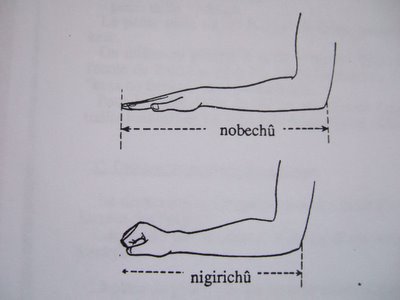

To find out the right size of the kesa, one has to measure the distance from the elbow to the tip of the fist ( nigirichu) or the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger ( nobechu) of the person who will wear the kesa. This measurement is called Chu or cubit ( Sanskrit hasta) and means forearm.

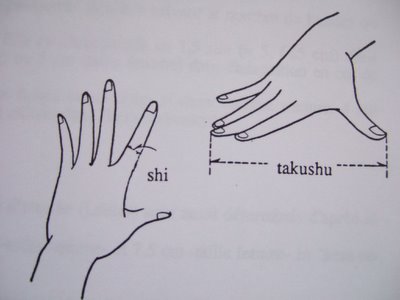

Takushu (stretch between thumb and middle finger when the hand is opened) and shi ( the width of the first finger) are also used. The general rule is the following:

24 shi (finger) = 2 takushu ( stretch)= 1 chu ( cubit)

If your nobechu is 43 cm, then the kesa will be:

3 times 43 long (135cm) by 5 times 43 wide ( 215cm ).

This size tends to be generally too big.

If you pick up the nigirichu , 38cm, then you have a kesa which will be 114 long by 190 wide which is …too small.

The method is to go for a chu which is in between: 43+38 divided by 2= 41

3 times 41 long ( 123 ) by 5 times 41 wide ( 205) will be the size of your kesa.

To make things simple, measure your nobechu and find out below which size your kesa should be:

40: 191cm/114cm

41: 198cm/116cm

42: 205cm/121cm

43: 205cm/123cm

44: 212cm/126cm

45: 212cm/129cm

46: 219cm/131cm

47:219cm/134cm

48: 226cm/136cm

49: 233cm/139cm

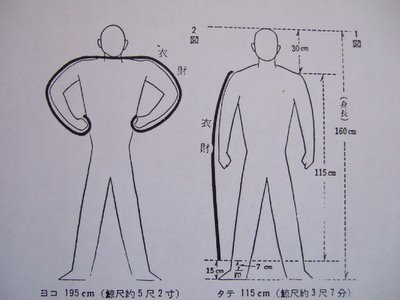

There is another way, which is expressed in the Hobukukakusho of Mokushitsu Zenji. It is simple, to find out the length of the kesa, one measures the distance from the shoulder to a point which is about 15 cm from the ground. The width is the distance from the fingertips of your hands forming fists. This method is not used by Kodo Sawaki’s disciples because it doesn’t follow Buddha’s instructions as quoted in Kesa-Kudoku Shobogenzo ( 3 chu by 5 chu ).

The monk Taigu Ryokan (1758-1831), beloved by all, beggar and wanderer, naive clown, clouds eater and lover of the brush wrote the following lines in Chinese :

The monk Taigu Ryokan (1758-1831), beloved by all, beggar and wanderer, naive clown, clouds eater and lover of the brush wrote the following lines in Chinese :On my journey home, I had come as far as the Itoi River, when I fell ill and had to stay the night in a certain home. As I listened to the rain, I suddenly felt a shiver run down my spine and composed this poem:

A robe and bowl are everything I have in the world

With this frail body, I burn incense

And sit

All night, a gentle rain fills the darkness outside

My long years of hard travel are now over

Monday, February 27, 2006

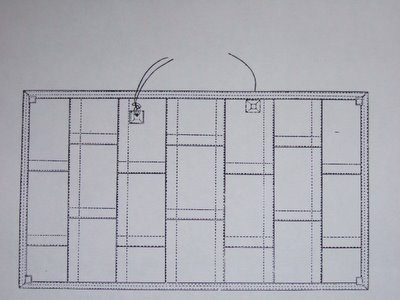

This is a seven stripes kesa (kassetsue), back and front. A kesa is a kind of patchwork following precise rules and a clear pattern. The main body is made of patches of different sizes sewn vertically and horizontally. The size of a kesa varies according to the person wearing it. Of course, a kesa can be made of many more stripes, nine, eleven, thirteen...twenty-five and more but we will only study the seven stripes kesa for a start.

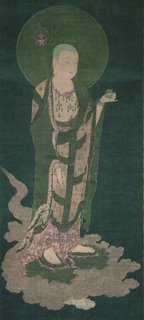

What is the true colour of a kesa? It is said that Shakyamuni's kesa had the same colour as his skin. The word kesa comes from the sanskrit kasaya whixh means colour ochre. Bodhidharma and Dogen's kesa were dark blue almost black. Generally speaking, most texts ( Ritsu ) agree on the fact that the colour should not be a pure and bright colour, it should be neither white nor a clear primary colour, rather a mixed and mudddy darkish colour: blue, grey, brown, purple, black, dark yellow, dark green...

If you buy a fabric in a shop, choose a thin and strong quality fabric, you may also buy it white and dye it at home ( dyed fabric tend to fade quickly) or go for what Halifax Roshi did: gather scraps, cuts, garments from everywhere around you and dye them all. Please read the interview ( http://www.shambhalasun.com/Archives/Features/1997/Nov97/JoanHalifax.htm)

of Halifax roshi in the Shambhala Sun. For a first kesa, I strongly recommand to make things simple, buying fabric is very convenient and absolutly fine.

“As material for the robe, we use silk or cotton, according to suitability. It is not always the case that cotton is pure and silk is impure. There is no viewpoint from which to hate cotton and to prefer silk; that would be laughable. The usual method of the buddhas, in every case, is to see rags as the best material”.

Dogen, Kesa-Kudoku.

The kesa is the robe of sitting Zen. It is not only the robe of monks, nuns, priests, abbots and the likes. Everybody can wear a kesa. There is no requirement. In Dogen’s ligneage, one sits wrapped in the kesa, and that’s it.

You may find in various Sangha the belief that the true kesa of the monk is black, that brown or light-coloured kesa are for teachers and so forth… These rules do apply in the Soto sect. In the tradition of the Nyohoe kesa, these rules simply don’t apply.

The kesa is made of rags. Just like our lives. Rags-like. Patches, shredded stories, cuts of various nature.

When you choose fabric for the kesa, please, remember that you are rags holding rags. So it can be cotton, linen, hemp, silk even artificial fabric…IT doesn’t cultivate any particular view. Rags are best. What collects fabric is a broken life, a life in pieces, what is collected is just rags. Nothing special, nothing holy in this. You may buy a beautiful and light fabric in a shop and dye it or not, you may ask people to give you bits and pieces of fabric, you may look into your wardrobe and get things you don’t wear anymore to make the robe…It is up to you. In Kesa-Kudoku, Dogen lists the ten sort of rags:

1)Rags chewed by an ox, 2) rags gnawed by rats,3) rags scorched by fire,4) rags soiled by menstruation,5) rags soiled by childbirth,6) rags offered at a shrine,7)rags left at a graveyard,8) rags offered in petitional prayer9)rags disregarded by king’s officers,10) rags brought back from the funeral. These ten sorts people throw away, there are not used in human society. We pick them up and make them into the pure material of the kasaya.

1)Rags chewed by an ox, 2) rags gnawed by rats,3) rags scorched by fire,4) rags soiled by menstruation,5) rags soiled by childbirth,6) rags offered at a shrine,7)rags left at a graveyard,8) rags offered in petitional prayer9)rags disregarded by king’s officers,10) rags brought back from the funeral. These ten sorts people throw away, there are not used in human society. We pick them up and make them into the pure material of the kasaya.

The kesa is the Buddha’s robe. The robe of Zazen. In Japanese, it is called Nyoho-e, the robe-garment of as it-is-ness. Thanks to the work and life of the Shingon teacher Kaiju Jiun Sonja (1718-1804) who loved being grasped by the still state, to the dedication of Mokishutsu Zenji and later, to Eko Hashimoto and Kodo Sawaki, we have now the opportunity to study, sew and wear the Buddhist robe.

I started to sew the robe 25 years ago and I would say that I am still very ignorant and unexperienced. As a monk, I consider myself as a student of the kesa. I know very little but would like to share it with whoever want to sew a kesa and sit. My intention is to offer a simple, clear sewing guide as well as the opportunity for everybody to contribute to this blog. All suggestions and observations are welcome.

Originally, it is said that one day the Buddha was peacefully walking in the country with Ananda. All around them were valleys and fields, clouds and sky, air and mists, and birds, and beasts. Ananda asked the Buddha : “ we need a special garment that will show to the rest of the world that we are your disciples”. With a wave of his hand, Buddha indicated nature all around them and said : “Our garment will be like this”. Buddha was just pointing to the paddy fields, so Ananda thought that he meant the paddy fields, the rice fields. Buddha was just pointing to the whole universe, formless, ever changing. Ananda thought he meant the kesa should look like the paddy fields. Shakyamuni Buddha had a complete free mind, an open mind. He could embrace the whole view with a single glance, he did not choose, did not fix any boundaries, a consciousness without a single choice, no judgement, just the recognition of things as they are. It is said that when Shakyamuni saw the first robe, he was filled with joy and asked every single monk to wear it.